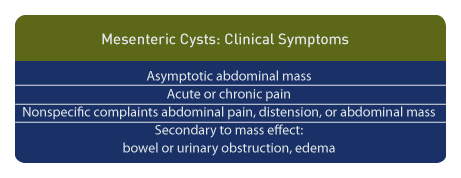

Anomalies of the Fetal Abdomen II: Abdominal Cysts and Cystic Structures

(To view a specific reference. Click on the reference number which will take you to the abstract or article.)

Mesenteric Cyst: Information and Imaging Considerations

Page Links: Incidence and Classification, Location, Ultrasound Diagnosis, Outcome

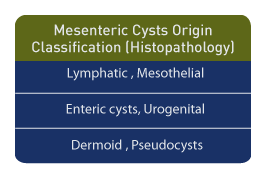

Incidence and Classification

Mesenteric cysts are rare, accounting for only one in 140,000 hospital admissions after birth. [1] They are most often lymphatic in origin. Based upon histopathology, a classification scheme has been reported as follows: cysts usually of lymphatic origin, but which may also be of mesothelial, enteric, urogenital, dermoid, or pseudocyst origin. [2] Cystic lymphangioma may occur in the first decade of life, and there is a female predominance.

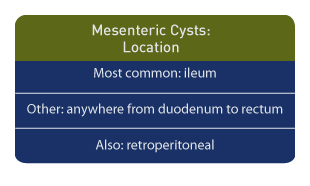

Location

The most common location is the ileum, but cysts may be located anywhere from the duodenum to the rectum, and retroperitoneal locations. Origination from ectopic lymphatic tissue is not unusual. [3]

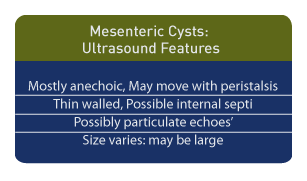

Ultrasound Diagnosis

Ultrasound is the diagnostic method of choice. In children, a single mesenteric cyst is most common and is reported in 79% of cases. [1] The cysts are typically anechoic and they may move with peristalsis, depending upon their location. Most mesenteric cysts are thin-walled. Internal septations and echoes suggestive of sediment may be seen, and while enteric duplication cysts are described as thick-walled, cystic lymphangioma or pseudocysts may display multiple loculations. [4] The cyst size can vary, and some are quite large. [5] Confusion with an ovarian cyst is possible, but cyst aspiration and assessment of fluid for estradiol and progesterone can distinguish between the two.

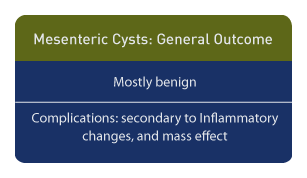

Outcome

Although mesenteric cysts are benign, the occasional focal malignancy or stromal gastrointestinal tumors are noted. [6] The coexistence of a duplication cyst and a mesenteric cyst can result in a complicated inflammatory mass [7], and complications such as renal failure have been reported as a result of the mass effect. [8]

Clinical symptoms include painless abdominal tumors. The presentation may be acute or chronic symptoms and may be related to the compressive effect of the cyst, which include: intestinal obstruction, urinary tract dilatation, and lower extremity lymphedema. If a lymphangioma is present, it may recur.

Neonatal complications include peritonitis from rupture. [9] Options for neonatal management include laparoscopic resection and laparotomy. The outcome, in the absence of complicating factors, is uniformly good.

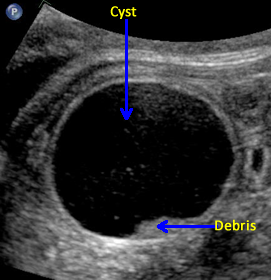

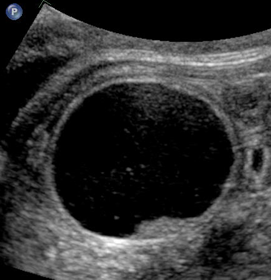

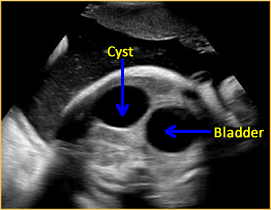

Mesenteric Cyst: Images

Above. Mesenteric cyst. Case 1. 33 1/7 weeks gestation. Cyst moves with maternal repositioning. This is a large cyst measuring 4.6 x 3.7 x 3.5 cm.

Above. Mesenteric cyst. Case 1. 33 1/7 weeks gestation. The cyst is inferior to the fetal stomach.

Above. Mesenteric cyst. Case 1. 33 1/7 weeks gestation. The cyst is not attached and is not near the fetal bladder.

Above. Mesenteric cyst. Case 1. 33 1/7 weeks gestation. The cyst is not attached to the fetal kidneys.

Above. Mesenteric cyst. Case 1. 33 1/7 weeks gestation. Sediment is noted in the gravity dependent portion of the cyst. This cyst was confirmed as a mesenteric cyst.

Above. Case 2. Mid-trimester scan. This image represents a probable mesenteric cyst, but an ovarian cyst should be considered due to the cyst location in the pelvis. Most ovarian cysts are detected in the third trimester.

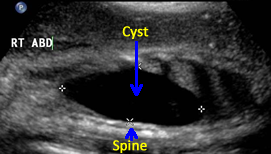

Above. Case 3. 28 3/7 weeks gestation. Cystic mass in the right upper quadrant measuring 5.9 x 2.9 x 3.4 cm. The cyst is posterior to the right lobe of the liver and extends inferiorly.

Above. Case 3. 28 3/7 weeks gestation. Transverse view of a cyst in the right upper quadrant.

Above. Case 3. 28 3/7 weeks gestation. Longitudinal view of a cyst in the right upper quadrant. Note the close proximity of the cyst to the fetal spine. On MRI, the kidney is displaced inferiorly and given the potential retroperitoneal location, a duplication cyst of the gastrointestinal tract is a possibility.

Ovarian Cyst

Ovarian Cyst: Information and Imaging Considerations

Ovarian cysts are the most common cystic structures found in the fetal abdomen and the prenatal diagnosis of these structures has increased with the use of ultrasound.

As with most cystic intra-abdominal structures, the diagnosis of an ovarian cyst is not made until the third trimester at a median gestational age of 35 weeks with a range of 26 to 40 weeks. [10]

The pathology of ovarian cysts is usually follicular in origin with the ovarian cortex demonstrating primordial follicles. [11] Others suggest that gonad maldevelopment may be the origin of complex neonatal cysts. [12]

In a meta-analysis of 420 fetuses with ovarian cysts, 50% regressed spontaneously, 35% were complicated by torsion or hemorrhage within the cyst, and 41% of the neonates required surgery. [13]

Cyst size was a determining factor in the outcome. If the cysts were < 50 mm, 98% regressed spontaneously and if the cysts were > 50 mm, 93% resulted in complications. [4] Hemorrhage within a cyst can result in fetal anemia.[14],[15]

Most authors recommend therapy including drainage or postnatal surgical excision if the cyst size is greater than 50 mm. [16] Prenatal aspirations of cysts that are greater than or equal to 50 mm result in significantly better outcomes than in those cysts of a similar size that are not aspirated. Again, simple cysts of < 50 mm resolved spontaneously 76% of the time. Among cysts that suggest torsion on ultrasound (complex echoes including septa, echogenicity), 24 of 34 (71%) required oophorectomy and 9 of 34 (26%) spontaneously disappeared. [17]

A cutoff of 40 mm or less is also associated with spontaneous regression in 50% of the cases. A cyst size of > 40 mm is associated with cystectomy, torsion, or cystic hemorrhage. [18]

In some studies, the risk of torsion is 50% with a cyst diameter of > 40 mm. [19]

Whether one uses the 50 mm cutoff or the 40 mm cutoff, a consistent finding is that cysts > 40 mm in diameter predict complications and neonatal surgery. A number of authors suggest cyst aspiration when the diameter is > 40 mm during the antenatal scan. [20],[21]

Simple ovarian cysts frequently become complex prior to birth. [22] The rate of spontaneous resolution of simple cysts (63%) is greater than the rate of spontaneous resolution of complex cysts (40%). [23]

In one study, the number of complex cysts increased from 18% in the prenatal period to 55% after birth, and torsion was more likely to be associated with complex cysts than with simple cysts. [24]

Conservative management with no attempts at aspiration of a complex ovarian cyst during the fetal period results in the loss of that ovary in the majority of cases. [25]

Postnatal Management

After birth, surgery is usually performed on large or complex ovarian cysts. [26]

For the management of ovarian cysts after birth, some authors suggest ultrasound guided aspiration for asymptomatic large ovarian cysts. They indicate a greater success rate in preserving ovarian function compared to surgery and they also suggest that surgery be reserved for acute torsion, intestinal obstruction, or volvulus. [27]

Laparoscopy is the surgical procedure of choice for the management of neonatal ovarian cysts. [28]

Laparoscopy allows for aspiration, cystectomy, or removal of the ovary. A cyst that is complex on ultrasound usually represents torsion, but surgery seems warranted in these cases since morbidity from torsion includes hemorrhage, peritonitis, and bowel obstruction. [29]

In addition to surgical management, laparoscopy is of value in confirming a diagnosis of auto-amputation, from adnexal torsion or from cystic degeneration. [30]

Advances in laparoscopic techniques, including the modified 2-port approach, allow a rapid and safe surgical methodology. [31]

Transumbilical laparoscopy allows complete cyst aspiration as well as cyst evisceration through the umbilicus for either ovarian cystectomy (simple cysts) or salpingo-oophorectomy (cyst torsion). [32]

Ovarian Cyst: Images

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 1. 35 weeks gestation. The cystic structure arises in the lower abdomen and is adjacent to the anterior abdominal wall just to the left of mid-line. The cyst measures 45 mm x 36 mm meeting critical cutoff values which increase the risk for torsion and/or infarction.

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 1. 35 weeks gestation. The cyst extends superiorly towards the fetal stomach. Note the low level echos within the cyst compared to the stomach.

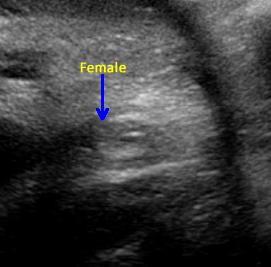

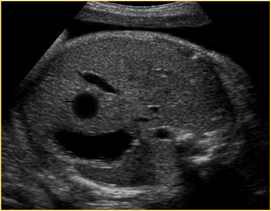

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 1. 35 weeks gestation. Fetal gender is ascertained and confirmed to be female.

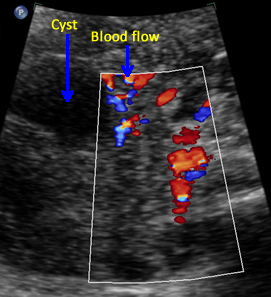

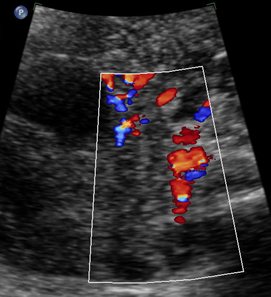

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 1. 35 weeks gestation. Blood flow to the cyst is confirmed.

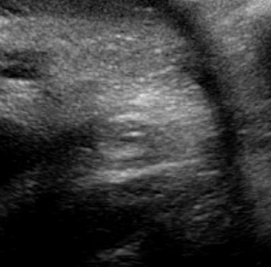

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 1. 35 weeks gestation. The cyst wall is layered and somewhat thickened and complex. Ovarian cyst diagnosis was confirmed after birth.

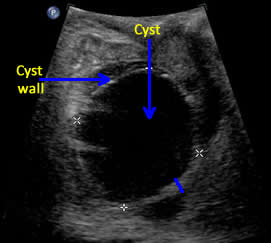

Above. Ovarian cyst. Case 2. Third trimester ultrasound. Ovarian cyst is right sided with echos suggestive of sediment or blood. The cyst exceeds the 40 mm to 50 mm cutoff in size suggesting an increased risk for adverse outcome.

Hepatic Cysts and Tumors: Information

Hepatic Cysts

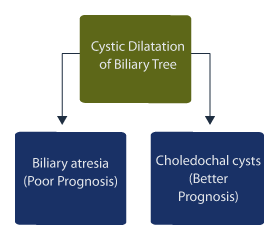

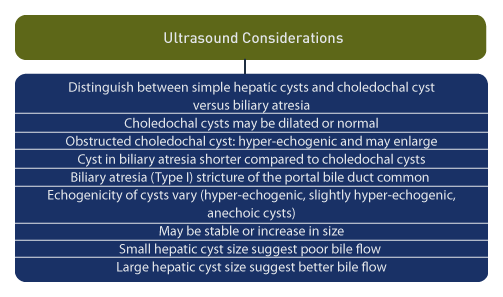

Hepatic cysts are rare findings on prenatal ultrasound [33], and cystic dilatation of the biliary tree may be due to choledochal malformations or biliary atresia. [34] Distinguishing the origin of cystic biliary dilatation is important because the prognosis is worse for biliary atresia compared to choledochal cysts.

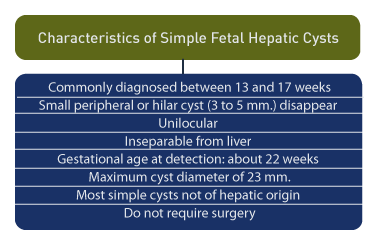

Hepatic cysts are commonly diagnosed between 13 and 17 weeks gestation. [35] Peripheral cysts of 3 mm to 5 mm frequently disappear upon follow-up scans. Hilar cysts may also disappear or become smaller during pregnancy or the neonatal period. A distinguishing feature for simple hepatic cysts is their unilocular nature and inseparability from the liver. [36]

Upon a review of 15 hepatic cysts detected prenatally, the gestational age at detection was an average of 22 weeks and the cyst diameter was an average of 23 mm. [37] Most of the cysts were simple and were not of hepatic parenchymal origin. Only 3 of 15 required surgical interventions. [5]

Hepatic cysts present with a variety of ultrasound findings. These include: hyperechogenic, slightly hyperechogenic, and small anechoic cysts. [38] Cysts may be stable or increase in size, such as obstructed choledochal cyst, which may be hyperechogenic and undergo enlargement during pregnancy. [6]

Both 2-D and 3-D evaluation may be useful in cyst evaluation. [39] MRI is useful in delineating cyst anatomy and in defining the adjacent hepatic anatomy. [40]

The length and width of cysts in patients with biliary atresia were shorter compared to patients with choledochal cysts. [41] In type I biliary atresia, stricture of the portal bile duct is the predominant feature while the bile duct in neonates with choledochal cysts may be dilated or normal. [9]

Small hepatic cyst size, which remains unchanged during prenatal ultrasound evaluation, may predict poor bile flow and fibrosis during the neonatal period. Hepatic cysts which are large prenatally demonstrate better bile flow and mild or moderate fibrosis during the neonatal period. [42]

Management of hepatic cysts is affected by the problem of distinguishing between choledochal cysts and biliary atresia. Therefore, some surgeons recommend early exploration. [43]

Others suggest early surgical intervention if suspected choledochal cysts demonstrate biliary obstruction, while non-obstructed patients may be explored at > 3 months of age. [44] Asymptomatic choledochal cysts may become symptomatic later in the neonatal period or later in life. [45] Distinct types of biliary atresia may also be associated with choledochal cysts. [46]

Large hepatic cysts that contain re-accumulating bile after aspiration require surgery in the early neonatal period. [47] Familial choledochal cysts may occur in siblings, necessitating both prenatal evaluation and post natal follow-up. [48]

Given the variable anatomy in infants with suspected congenital defects of the biliary tract, the anatomy should be carefully defined before surgical excision. [49]

Hepatic Tumors

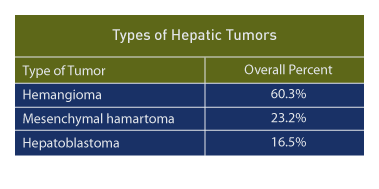

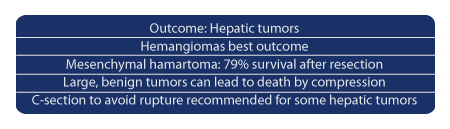

In a large retrospective review [50], three main hepatic tumors are seen in the fetal and early neonatal period: hemangioma (117 cases, 60.3%), mesenchymal hamartoma (45 cases, 23.2%), and hepatoblastoma (32 cases, 16.5%).

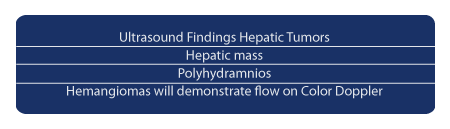

The most common finding on prenatal ultrasound is a mass and polyhydramnios. Neonatal death is related to hydrops, respiratory distress, and congestive heart failure.

Solitary hepatic hemangiomas have the best outcome and hepatoblastoma have the worst outcome (25% survival). About half of the cases of hepatoblastoma have abnormally elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein. Seventy-nine percent of mesenchymal hamartoma patients survived who underwent resection.

Benign mesenchymal hamartomas can lead to death due to the compressive effect of the tumor. [51],[52] Rapid growth can lead to giant tumors which require decompression prior to birth. [53] Another treatment modality is therapeutic embolization prior to resection. [54] An unusual reported association is mesenchymal hamartoma of the liver and mesenchymal stem villous hyperplasia of the placenta. [55]

Cesarean section is usually performed for hepatic tumors in order to reduce the likelihood of tumor rupture. [56]

Hepatic Cysts and Tumors: Imaging Considerations and Images

Above. Choledochal cyst. This schematic is of a large, unilocular anechoic cyst within the liver parenchyma in the upper right quadrant of the fetal abdomen. Small tubular bile ducts can sometimes be seen entering the cyst. Color Doppler will not demonstrate blood flow.

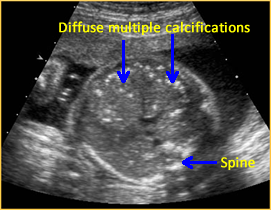

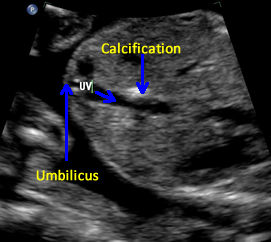

Above. Hepatic calcifications may be within the liver parenchyma itself or may be attached to the liver capsule from conditions such as meconium peritonitis. Calcifications within the liver substance suggest a systemic etiology, such as fetal infections from toxoplasmosis, varicella, CMV, parvovirus, or herpes simplex.

Above. Gestational age is 36 6/7 weeks. Confirmed meconium peritonitis. Note calcifications on capsular surface of the liver, which is the most common cause of the presence of such calcifications.

Above. Gestational age is 23 weeks. Isolated hepatic calcification.

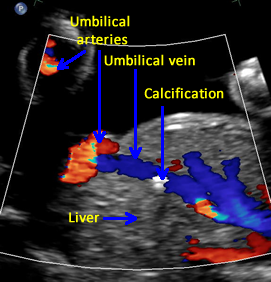

Above. Gestational age is 23 weeks. Isolated hepatic calcification. The calcification measures 4.2 x 7.4 x 6.9 mm. It is adjacent to the hepatic vein.

Above. Gestational age is 23 weeks. Isolated hepatic calcification. Color Doppler demonstrates the relationship of the echogenic focus to the hepatic vein. The lesion was not within the gallbladder and there were no adverse outcomes.

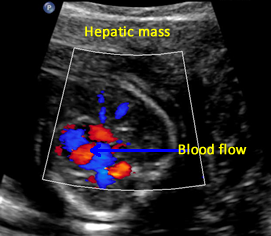

Above. This image represents a potential hepatic neoplasm. Of concern is the unexplained associated polyhydramnios. As noted previously, the three main hepatic tumors are hemangioma, mesenchymal hamartoma, and hepatoblastoma.

Above. Polyhydramnios is associated with fetal hepatic neoplasms. In addition to the tumors discussed above, hepatic masses may also be due to metastatic neuroblastomas, which are the most common tumors to metastasize to the liver.

Above. Gestational age is 22 weeks. Potential hepatic tumor of mixed echogenicity.

Above. Gestational age is 22 weeks. Potential hepatic tumor of mixed echogenicity. Color Doppler demonstrates blood flow to the heterogeneous mass. The differential diagnosis includes hemangioma or one of its varieties or hepatoblastoma.

Above. Same tumor as above demonstrating a complex heterogeneous mass. Previous scans had demonstrated moderate vascularity. There was no evidence of fetal hydrops developed during the pregnancy.

Urachal Cyst: Information and Imaging Considerations

The urachus is the top or apical part of the bladder which regresses after birth. As a result of congenital defects, a number of urachal anomalies are possible. Most involve abnormalities that extend from the apex of the bladder. These anomalies are rare and more frequent in males than in females. [57]

Four types of urachal anomalies have been described: patent urachus (50%), which is a communication from the apex of the bladder to the base of the umbilicus, and three types of other defects: sinus (15%), diverticulum (3%-5%), and cyst (30%). [58]

Urachal cysts present on the prenatal ultrasound as extra-abdominal cysts near the umbilical cord insertion site. These cysts typically connect with the fetal bladder through a channel which may change in size as the fetus voids. [59] Since the content of the cyst is urine and the channel contains urine, the cyst and channel will be anechoic.

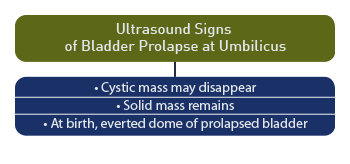

The cystic mass at the base of the umbilical cord may disappear as the pregnancy progresses, while the possibility remains of the bladder prolapsing through the urachal opening at the base of the umbilicus. [60] When the cyst disappears, a solid mass remains on ultrasound, which may represent the everted dome of the bladder prolapsing through a patent urachus. [61]

Urachal Cyst: Images

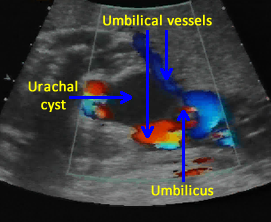

Above. Urachal cyst. Note the anechoic connection between the fetal bladder and the umbilicus.

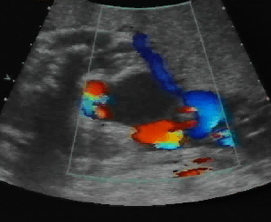

Above. Urachal cyst. Color Doppler demonstrates blood flow through the umbilical vessels but no blood flow to the cyst itself, which excludes the possibility of umbilical vein varix.

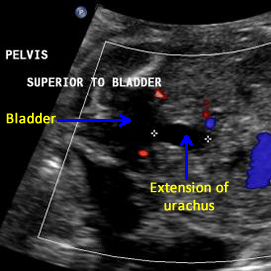

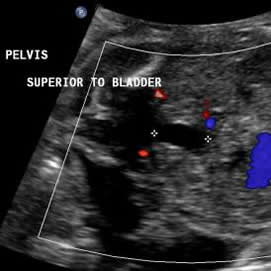

Above. Note the fetal bladder and the anechoic extension of a cyst-like structure superiorly.

Above. Urachal cyst. 23 weeks. Same patient as above showing an anechoic structure extending to the umbilicus. Color Doppler showed no flow within the cyst.

Above. Urachal diverticulum. 25 3/7 weeks. The anechoic structure extends from the fetal bladder, but does not extend to the umbilicus.

Above. 19 3/7 weeks. False positive finding for urachal cyst. Although there is an apparent anechoic structure at the umbilical cord insertion site, color Doppler demonstrated this to be an umbilical vein, which is dilated more than usual, but with no untoward outcome.

Above. Same patient as above. 19 3/7 weeks gestation. Transverse view of the umbilical cord demonstrating two umbilical arteries and a dilated umbilical vein. Again, color Doppler demonstrated no evidence for urachal cyst.

Urachal Cyst: Video

Above. Color Doppler of a urachal cyst demonstrating no flow within

the cyst and confirming the anechoic nature of the cyst.

Real time ultrasound confirmed connection with the bladder.

Pancreatic Cyst: Information and Imaging Considerations

Page links: References

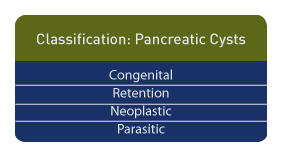

Pancreatic cysts are rare and should be distinguished from pseudocysts. They may be classified as congenital, retention, neoplastic, and parasitic. [62] Retention cysts are enlargements of the pancreatic ducts due to obstruction. [1]

The congenital pancreatic epithelium lined cyst rarely has been reported and most, as expected, are seen in the left upper quadrant of the fetal abdomen, [63] while pancreatic pseudocysts and pancreatic cystadenoma may present as large cystic or cyst-like abdominal masses in children. [64] Prenatal diagnosis is usually made during the third trimester. The differential diagnosis includes mesenteric cyst, while a distinguishing feature for pancreatic cysts may be their occasional location in the retroperitoneal space. [65]

Ultrasonography and MR imaging is useful in children. A bilocular large cystic mass has been reported with the spleen displaced superiorly, and the left kidney displaced posteriorly. [66]

Uncommonly, a foregut duplication cyst may arise entirely from the pancreas confounding the diagnosis of a pancreatic cyst. [67] Other rare possibilities include intrapancreatic duodenal duplication cyst causing the inversion of superior mesenteric vessels. [68]

Unilocular cystic masses of the pancreas can masquerade as a benign cyst while, in fact, these masses can be a malignant tumor. Pancreatoblastoma is one such tumor and early diagnosis is important because of its relatively low metastatic potential. [69]

Pancreatoblastoma has also been reported in association with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) and in that instance, molecular investigation disclosed a mosaic paternal 11p15 uniparental disomy in the tumor cells. [70] However, irrespective of the tumor association, BWS has an independent association with uniparental disomy

Adrenal Cysts and Masses: Images

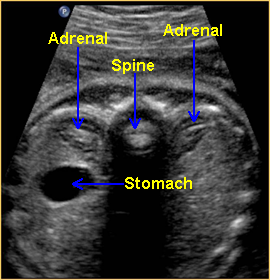

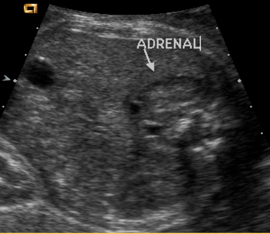

Normal Adrenal Gland

Above. Transverse view. The normal adrenal glands appear as crescent shaped structures superior to the kidneys. When well visualized, the more echogenic gland may be surrounded by mixed or reduced echos.

Above. Partial coronal view. Again, normal adrenal gland demonstrating crescent shape.

Above. Coronal view demonstrating the relationship between the kidney and the normal adrenal gland.

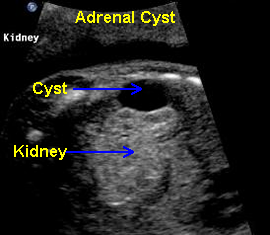

Adrenal Cyst, 19 6/7 weeks

Above. Oblique view. Cystic structure, superior and extrinsic to the right kidney of adrenal origin.

Above. Longitudinal view. Right sided cyst, superior and extrinsic to the kidney.

Above. Transverse view. Note relationship of the kidney to the adrenal cyst which measures 1.7 X 1.3 cm.

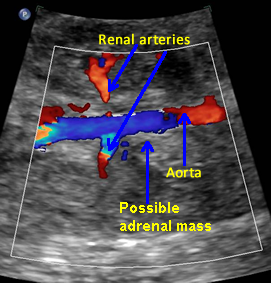

Possible Adrenal Mass

Above. Coronal view. Color Doppler identifies possible mass in region of adrenal gland.

Above. Coronal view. Again, discrete appearing intra-abdominal mass, potentially of adrenal origin.

Above. Longitudinal view. Appearance continues to suggest mass, but follow-up ultrasounds demonstrated resolution of the findings.

Large Definitive Adrenal Mass

Above. Longitudinal view. Large 3.4 X 2.8 cm mass, hyperechoic structure with small cystic-like clusters. Possibilities include neuroblastoma.

Above. Transverse view. Same patient as immediately above. Large echogenic adrenal mass, possible neuroblastoma versus sub-diaphragmatic pulmonary sequestration. Feeding vessel was not demonstrated.

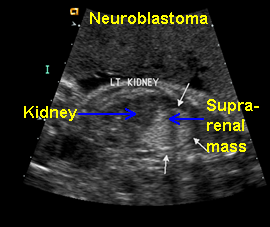

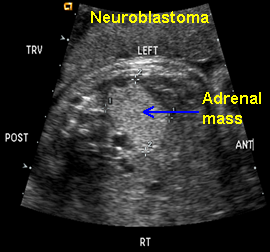

Neuroblastoma

Above. Neuroblastoma confirmed, postnatally. Longitudinal view. Supra-renal echogenic mass, no feeder vessel defined.

Above. Neuroblastoma confirmed, postnatally. Transverse view. Supra-renal echogenic mass, no feeder vessel defined.

Neuroblastoma versus Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS)

Above. Longitudinal view. Supra-renal echogenic mass. Unilateral masses on the left side are more likely for pulmonary sequestration.

Above. Transverse view. Supra-renal mass. Feeder vessel should be sought, which defines pulmonary sequestration (see below), while increased blood flow on color Doppler may be demonstrated with neuroblastoma.

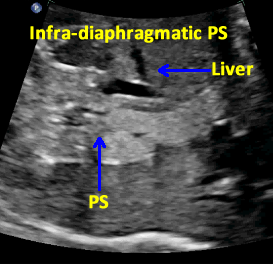

Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS)

Above. Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS). Transverse view demonstrates homogeneous, echogenic mass adjacent to the liver and below the diaphragm.

Above. Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS). Transverse view. Slightly larger image demonstrates homogeneous, echogenic mass adjacent to the liver and below the diaphragm, and in close approximation to the abdominal aorta.

Above. Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS). Longitudinal view shows the same basic homogeneous, echogenic nature of the mass.

Above. Infra-diaphragmatic Pulmonary Sequestration (PS). Color Doppler indicates the aorta to be the origin of the feeder vessels to the mass.

-

Abstract: PMID: 9036901 -

Abstract: PMID: 12630343 -

Abstract: PMID: 6732494 -

Abstract: PMID: 1936773 -

Abstract: PMID: 16151789 -

Abstract: PMID: 19609826 -

Abstract: PMID: 18172638 -

Abstract: PMID: 15359411 -

Abstract: PMID: 15359411 -

Abstract: PMID: 12100417 -

Abstract: PMID: 19205454 -

Abstract: PMID: 16037528 -

Abstract: PMID: 17621997 -

Abstract: PMID: 11422977 -

Abstract: PMID: 11422977 -

Abstract: PMID: 16891814 -

Abstract: PMID: 11781981 -

Abstract: PMID: 16108397 -

Abstract: PMID: 17633396 -

Abstract: PMID: 18510091 -

Abstract: PMID: 17219808 -

Abstract: PMID: 16113572 -

Abstract: PMID: 18207672 -

Abstract: PMID: 18186135 -

Abstract: PMID: 16113572 Kim HY, Park KW, Jung SE, Lee SC, Kim WK. Natural course and treatment of fetal ovarian cysts. J Korean Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2005 Jun;11(1):1-8. -

Abstract: PMID: 16819601 -

Abstract: PMID: 12378456 -

Abstract: PMID: 10949421 -

Abstract: PMID: 10444015 -

Abstract: PMID: 18439514 -

Abstract: PMID: 18721022 -

Abstract: PMID: 10817884 -

Abstract: PMID: 15001123 -

Abstract: PMID: 18642370 -

Abstract: PMID: 10867671 -

Abstract: PMID: 17336186 -

Abstract: PMID: 12149700 -

Abstract: PMID: 18491406 -

Abstract: PMID: 16124073 -

Abstract: PMID: 14632336 -

Abstract: PMID: 16863844 -

Abstract: PMID: 11479866 -

Abstract: PMID: 12501550 Tze-Ho Chen, Ming-Tzong Cheng, Yu-Li Lin. Antenatal diagnosis of choledochal cyst: a case report. Changhua J Med. 2003;8(3):186-9. -

Abstract: PMID: 16979949 -

Abstract: PMID: 11896953 -

Abstract: PMID: 16452322 -

Abstract: PMID: 19203371 -

Abstract: PMID: 18022426 -

Abstract: PMID: 19365132 -

Abstract: PMID: 15692210 -

Abstract: PMID: 12378477 -

Abstract: PMID: 11464991 -

Abstract: PMID: 10781996 -

Abstract: PMID: 12677586 Friedland GW, Devries PA, Matilde NM, Cohen R, Rifkin MD. Congenital anomalies of the urinary tract. In: Pollack HM, eds. Clinical urography. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1990;559-787. -

Abstract: PMID: 11259707 -

Abstract: PMID: 19023211 -

Abstract: PMID: 18082690 -

Abstract: PMID: 16677873 Link: http://www.reference.md/files/D010/mD010181.html -

Abstract: PMID: 17848229 -

Abstract: PMID: 16151789 -

Abstract: PMID: 17297272 -

Abstract: PMID: 16538581 -

Abstract: PMID: 11227006 -

Abstract: PMID: 11297084 -

Abstract: PMID: 16896817 -

Abstract: PMID: 12673632

26

45

57

62