Fetal Urinary System Abnormalities I: Pyelectasis, UPJ Obstruction, Multi-cystic Dysplastic Kidney

Pyelectasis

(To view a specific reference. Click on the reference number which will take you to the abstract or article.)

Page Links: Definition, Incidence and General Characteristics, Outcome, Postnatal Evaluation, Isolated Pyelectasis and Trisomy 21, Down Syndrome

References are listed at the end of the chapter.

Definition

Pyelectasis is dilatation of the renal pelvis of the kidney. A value of ≤ 4mm. in the anterior posterior (AP) diameter of a transverse scan of the fetal kidney is considered a normal value irrespective of gestational age and a value of between 5 mm. to 10 mm. is considered borderline depending upon gestational age. Numerous cutoff values are reported in the literature. The most quoted, classic and recommended cutoffs for postnatal follow up studies are an AP pelvic diameter of ≥ 4 mm. at < 33 weeks and/or ≥ 7 mm. after 33 weeks.1

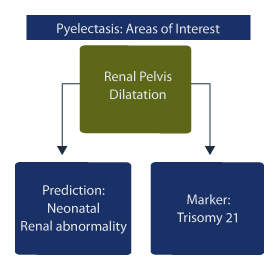

There are two areas of clinical interest:

1. dilatation of the renal pelvis for prediction of neonatal renal abnormality and,

2. dilatation of the renal pelvis as a soft marker predictor for Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome).

Incidence and General Characteristics

The incidence of pyelectasis is variously reported as between 1.7%2 and 4.5%.3 Renal pelvis AP dilatation is correlated with advancing gestational age4, and males are more commonly affected in both the normal and abnormal groups.5 There may be a genetic predisposition since occurrence is more common in consecutive pregnancies of affected fetuses.6

Outcome

The data on prognosis and outcome for pyelectasis is difficult to quantify due to the varied AP diameter cutoff levels and gestational ages, which are variously reported among relevant studies, but adverse neonatal outcome is possible. In general the second trimester ultrasound is the screen for pyelectasis but a 3rd trimester ultrasound better predicts neonates who require surgery for hydronephrosis.7 Over half of the children with hydronephrosis had prenatal ultrasound findings, 61% of which were pyelectasis. [Czarniak P, Zurowska A, Szcześniak P, Drozyńska-Duklas M, Maternik M, Gołebiewski A, Komasara L, Preis K, et al. Preliminary results of a program for the early management of children with congenital hydronephrosis. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2009 Apr;26(154):322-4.]8

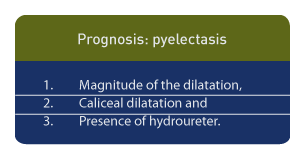

Prognosis for pyelectasis is dependent upon 3 factors9:

1. the magnitude of the dilatation,

2. caliceal dilatation and

3. the presence of hydroureter.

Fetuses with pyelectasis plus an additional ultrasound feature suggestive of urinary anomaly, such as enlarged bladder or kidney and/or ureteral or caliceal abnormality, required significantly more pediatric urology care after birth.10

Among 778 neonates referred for renal evaluation, 92% were referred on the basis of pyelectasis.11 In those studies, 76% of the neonatal scans were normal and 13% were associated with obstructive uropathy. Pyelectasis was found to be a poor predictor of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

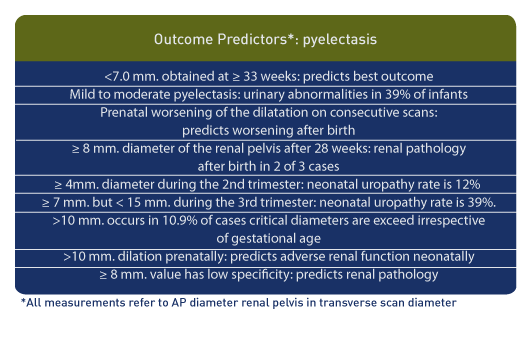

The best outcome for pyelectasis is a value of <7.0 mm. obtained at ≥ 33 weeks in patients scanned between 18 and 30 weeks.12

Mild to moderate pyelectasis is associated with urinary abnormalities in up to 39% of infants.13 In fetuses who had 2 scans demonstrating renal pelvis dilatation before birth, those with no change demonstrated worsening after birth in 18.6% and those with worsening of the dilatation on consecutive scans demonstrated worsening after birth in 23.9%.14 Further, fetuses demonstrating ≥ 8 mm. AP diameter of the renal pelvis after 28 weeks showed renal pathology after birth in 2 of 3 cases.15

When the AP diameter of the renal pelvis is ≥ 4mm. during the 2nd trimester the neonatal uropathy rate is 12% but if the renal pelvis is ≥ 7 mm. but < 15 mm. during the 3rd trimester the neonatal uropathy rate is 39%.3

Renal pelvis progression to > 10 mm. occurs in 10.9% of cases when the renal pelvis AP diameter is > 4 mm. at < 32 weeks or > 7 mm. at ≥ 32 weeks.16

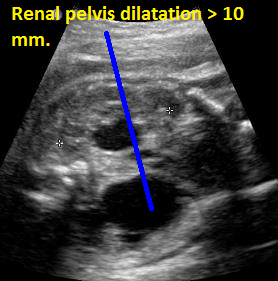

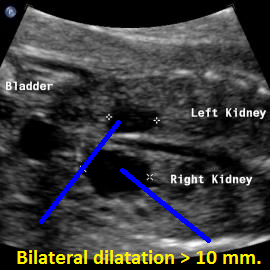

When hydronephrosis occurs (AP diameter of > 10 mm.) at 20 to 30 weeks gestation or > 16 mm. at > 33 weeks gestation, renal function is affected.17

In summary, a second fetal renal scan or a 3rd trimester scan with a cutoff of ≥ 10 mm. will detect most cases of neonatal renal pathology while a ≥ 8 mm. value has low specificity but will include most cases of pathology.18

Postnatal Evaluation

Prenatal ultrasound of the urinary tract has the highest false positive rate among malformations and approximately 20% of abnormal fetal urinary tract observations noted before birth are not present after birth19and prenatal ultrasound is less sensitive than the postnatal scan in defining obstructive uropathy. If the neonatal scan demonstrates an AP diameter of the renal pelvis of < 10 mm., this is reassuring since virtually all patients normalize within 1 year.20

The most specific time to conduct a neonatal ultrasound is 6 weeks after birth rather than 6 days after birth since non-obstructed kidneys demonstrate no change during this interval while obstructed kidneys show a mean increase in diameter during this interval.

In cases of pyelectasis if the neonatal ultrasound is normal, no further evaluation is needed. If the neonatal ultrasound shows isolated pyelectasis of < 10 mm. or < 15 mm. in uninfected cases of vesicoureteral reflux, voiding cystourethrogram can be delayed since cases within these parameters spontaneously resolve. [Masson P, De Luca G, Tapia N, Le Pommelet C, Es Sathi A, Touati K, Tizeggaghine A, Quetin P. Postnatal investigation and outcome of isolated fetal renal pelvis dilatation. Arch Pediatr. 2009 Aug;16(8):1103-10.]21

Isolated Pyelectasis and Trisomy 21, Down Syndrome

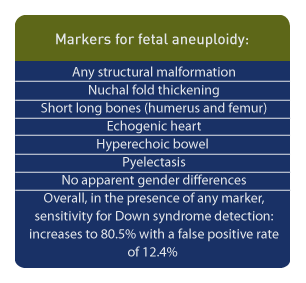

Markers for fetal aneuploidy include: any structural malformation, nuchal fold thickening, short long bones (humerus and femur), echogenic heart, hyperechoic bowel and pyelectasis; there are no apparent gender differences among sonographic markers for Down syndrome noted during the second trimester.22

Among 44 fetuses with Down syndrome, 25% had pyelectasis23 but studies which evaluate the significance of soft markers for fetal aneuploidy are varied and often contradictory.24 However, a recent study of over 60,000 scans reported that a > 4 mm. dilatation of the renal pelvis was associated with fetal aneuploidy, especially trisomy 21, and that the odds ratio for trisomy 21 with this criteria was 2.91 (CI=1.48-5.71).2 In summary, the sensitivity for Down syndrome detection is increased to 80.5% with a false positive rate of 12.4% in the presence of any marker, while pyelectasis as an isolated finding has a relatively low likelihood ratio.25

Page Links: Imaging Considerations, Measurements, References

Imaging Considerations

References are listed at the end of the chapter after those for Pyelectasis.

The overall sonographers’ tasks are as follows:

Sonographer Tasks:

- Measure renal pelvis through transverse view of the kidney.

- Take measurement when fetal bladder is empty, if possible.

- Measure largest anterior posterior diameter of the renal pelvis in mm.

- Obtain longitudinal view of fetal kidney.

- Observe for presence of calectasis.

- Assess contralateral kidney

- Measure longitudinal diameter of renal pelvis.

- Measure longitudinal diameter of the fetal kidney.

- Use color Doppler to assess for renal artery blood flow to each kidney.

The values for renal pelvis dilatation are taken from a number of studies. 1–5 Renal pelvis measurements change with gestational age. In general, ≥ 7 mm. is considered abnormal irrespective of gestational age. At <33 weeks, ≥ 5 mm. is generally considered the cutoff and a repeat measurement at ≥ 33 weeks is recommended. Neonatal follow up is recommended if the repeat measurement is ≥ 7 mm.

Measurements

Initial studies showed no relationship between maternal hydration and the degree of pyelectasis 6 , but follow up studies were not always confirmatory. In addition, the size of the renal pelvis measurement over a 2 hour period is variable 7 and the size also varies with bladder filling. 8 Fetal bladder sagittal length can help calculate a normal versus an enlarged fetal bladder. 9 In light of these findings, AP measurements of the renal pelvis should be conducted as often as possible when the fetal bladder is empty.

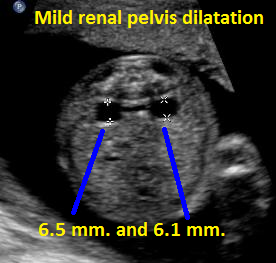

Above. Patient A. Transverse view of kidneys with mild bilateral renal pelvis dilatation.

Above. Patient B. Transverse view of kidneys with mild bilateral renal pelvis dilatation.

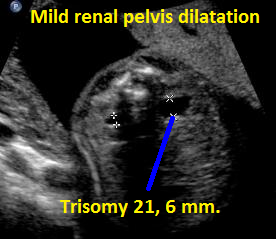

Above. Patient C. Transverse view. Mild renal pelvis dilatation; fetus with known Trisomy 21.

Above. Patient C. Sagittal view. Mild renal pelvis dilatation; fetus with known Trisomy 21.

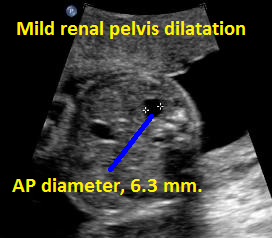

Above. Patient D. Borderline mild unilateral renal pelvis dilatation.

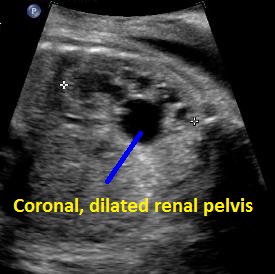

Above. Patient D. Coronal view. Borderline unilateral renal pelvis dilatation.

Above. Patient E. Transverse to oblique view with AP diameter of renal pelvis > 10 mm, designating a label of “hydronephrosis.”

Above. Patient E. Coronal view demonstrating dilatation of the renal pelvis and the presence of 2 kidneys by Color flow Doppler.

Above. Patient F. Transverse view of kidneys. Unilateral increase in dilatation of the renal pelvis which defines hydronephrosis (AP diameter of > 10 mm). Further assessment requires evaluation of pelvic, ureteral, or bladder obstruction.

Above. Patient F. Coronal view. Unilateral increase in dilatation of the renal pelvis which defines hydronephrosis (AP diameter of > 10 mm).

Above. Pyelectasis.

Above. Pyelectasis.

Above. Pyelectasis.

Ureteropelvic Junction (UPJ) Obstruction

Page Links: Definition, Measurements and Critical Cutoff Values, Incidence, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Biomarkers, Management, Surgery, Mass Screening,

(Click on specific reference number for a link to the original abstract or article.)

Definition

Ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction: obstruction of the urinary tract where the renal pelvis meets the ureter. This excludes dilatation of the ureter and/or bladder.

Measurements and Critical Cutoff Values

Measurement is taken in the anterior-posterior (AP) diameter of a transverse scan of the fetal kidney.

Normal value irrespective of gestational age: ≤ 4 mm.

Borderline value: 5 mm. to 10 mm. depending upon gestational age.

Abnormal value: 4 mm. at < 33 weeks and/or ≥ 7 mm. after 33 weeks. [1]

Hydronephrosis: ≥ 10 mm. irrespective of gestational age.

Values above the critical cutoffs may signify either an obstructive or non-obstructive (reflux) etiology.

Incidence

The incidence of prenatally diagnosed abnormalities of the urinary tract is 0.5% of all pregnancies. [2] Hydronephrosis is one of the most commonly diagnosed congenital malformations, and UPJ obstruction is the leading cause of hydronephrosis, accounting for approximately 35% of cases. [3]

Some causes of hydronephrosis, in descending order of frequency, include: UPJ obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux, ureterovesical junction (UVJ) obstruction, and posterior urethral valves (PUV). [4]

UPJ obstruction occurs more frequently in males; to female ratio is a 2.7; it is unilateral in about 61% and more frequent on the left side (68%). Bilateral obstruction occurs in approximately 39% of fetuses. [5] Prematurity and twinning are independently associated with UPJ obstruction. [6] Renal and urinary tract anomalies are more common in patients with Down syndrome (3.2%) compared to the overall population (0.7%). [7]

Pathophysiology

Antenatal urinary tract obstruction affects growth, maturation, and development of the kidneys by causing nephron reduction, atrophy of the tubules, and progressive interstitial fibrosis, all of which lead to programmed cell death and loss of tubular epithelial cells. [8]

A potential pathophysiologic explanation for congenital UPJ obstruction is as follows [9]: defective smooth muscle and nerve maldevelopment at the level where the ureter joins the renal pelvis leads to a functional obstructive defect, which delays urine ejection from the renal pelvis into the upper ureter on the basis of a non-peristaltic segment. Initial dilatation is compliant and does not result in renal parenchymal pressure from intra-pelvic pressure. However, increased intra-pelvic pressure results in tubular stretch and injury. As a consequence, a number of inflammatory, cellular, and chemical changes occur. Tubular cell death results in tubular atrophy. A vascular constrictive element may be contributory. [10] In congenital UPJ obstruction, renal histology is modified and the process includes not only inflammation and cell death, but also renin-angiotensin system activation and fibrosis. [11] Renal biopsies in patients undergoing pyeloplasty for UPJ obstruction may suggest a relatively well-maintained parenchyma with findings of parenchymal thinning and only limited tubulointerstitial injury. [12] A variety of renal parenchymal changes occur with UPJ obstruction, and these changes are not concordant with observations from conventional imaging. [13] The angiotensin type II receptor print (AGT R-2) accounts for a wide variety of congenital renal abnormalities, and this gene likely plays a role in the development of obstructive nephropathy. [14]

Diagnosis

Antenatal diagnosis of UPJ obstruction is suspected when critical measurements of the AP diameter of the renal pelvis are exceeded (> 4 mm. at < 33 weeks and/or ≥ 7 mm. after 33 weeks) [15] in the absence of ureteral or bladder dilatation. If the AP diameter value is ≥ 10 mm. under these circumstances, hydronephrosis is defined and UPJ obstruction can be specified as a cause of hydronephrosis.

Biomarkers

A key determinant in post-natal treatment is determining whether UPJ obstruction is due to an obstructive or non-obstructive origin. Noninvasive biomarkers for UPJ obstruction may define the clinical outcomes in advance of definitive clinical abnormalities. [16] Certain voided urinary markers differentiate children with UPJ obstruction needing a pyeloplasty versus those with non-obstructed kidneys, which can be managed conservatively. [17]

Urinary polypeptides may predict with a high degree of precision (94%) which patients with UPJ obstruction require surgical correction. [18] Other biomarkers have been identified in children with obstructive uropathy and include urinary heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which decreases significantly after surgical correction of the obstructive process. [19] Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and β2-microglobulin (β2-M) show promise in defining obstructed versus non-obstructed kidneys [20], while good diagnostic accuracy is achieved by measuring urinary concentrations of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). [21] Finally, urinary poly peptides in newborns with UPJ obstruction may also predict clinical outcomes. [22]

Management

The management of neonatal UPJ obstruction is controversial. [23] The finding of significant dilatation of the renal pelvis may be from an obstructive or non-obstructive origin, which is not always apparent. In patients with UPJ obstruction, differential renal function is usually normal at birth and does not often show signs of high-grade obstruction. When differential renal function is stable or improving, severe hydronephrosis resolves in more than 65% of cases. [24] Therefore, UPJ obstruction in newborns with normal renal function can be managed conservatively in most cases. [25]

In patients with moderate renal functional abnormality who undergo pyeloplasty, 83% showed improved renal function while infants with severely reduced renal function do not benefit by pyeloplasty. [26] Again, those with normal renal function most often show spontaneous resolution of the hydronephrosis.

Conservative management includes serial observation and evaluation utilizing renal ultrasound, voiding cystourethrogram, and renal flow scans (RFS). [27] In addition, retrograde studies may sometimes be useful. [28]

Indications for surgery include low differential renal function (DRF), absence of tracer clearance from the renal pelvis, parental preference, and acute renal failure. Pyeloplasty is considered the treatment of choice when the split difference in renal function is less than 40% and/or when the pelvic diameter is greater than 35 mm at initial evaluation. [29] Under these circumstances, the overall operative success rate is reported at 97.9%. Prophylactic antibiotics should be given before six months of age in those infants suspected of severe obstruction. [30]

Postnatal diagnosis of UPJ obstruction may be different from prenatal diagnosis. Postnatal UPJ obstruction more frequently affects females in later life, and presenting symptoms are urinary infection and/or abdominal pain with ureteral kinking as the likely etiology. [31]

Surgery

Pyeloplasty is the standard surgical procedure for UPJ obstruction. However, renal impairment remains after pyeloplasty in patients with urterovesicle reflux and pre-existing renal dysplasia. [32]

Other technically feasible surgical approaches include robotic laparoscopic single site pyeloplasty. [33] A high success rate with low morbidity is achieved in infants undergoing robot-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty [34], and other short-term studies demonstrate this approach to be safe and effective. [35] The number of laparoscopically performed pyeloplasty procedures for UPJ obstruction is increasing. However, some studies suggest no significant decrease in hospital length of stay whereas costs do increase. [36]

Mass Screening

Mass screening of infants at two months of age for congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKU T) yields a frequency of 0.96% for affected infants. [37] However, the number of patients requiring surgery (0.24%) does not justify mass screening.

Page Links: Sonographer Tasks, Normal Values, Ultrasound Findings: UPJ Obstruction, Follow-up

Sonographer Tasks

Measure renal pelvis through transverse view of the kidney.

Take the measurement when the fetal bladder is empty if possible.

Measure the largest anterior/posterior diameter of the renal pelvis in millimeters and record.

Obtain longitudinal view of fetal kidney.

Observe for the presence of caliectasis.

Measure the longitudinal diameter of the renal pelvis.

Measure the longitudinal diameter of the fetal kidney.

Use color Doppler to assess for renal artery blood flow to each kidney.

Perform amniotic fluid index.

In isolated UPJ obstruction with borderline AP diameter values of 5 mm. to 10 mm., only 1 follow-up is needed at 33 weeks or later.

Normal Values

- The most quoted, classic and recommended cutoffs for postnatal follow-up studies are an AP pelvic diameter of 5 mm or greater at < 33 weeks or ≥ 7 mm. at or after 33 weeks.

- Always repeat a value of 5 mm. at < 33 weeks. Repeat at or after 33 weeks.

- Hydronephrosis (abnormal) is defined as the AP diameter of the renal pelvis of ≥10 mm.

Ultrasound Findings: UPJ Obstruction

- Hydronephrosis is present if AP diameter is ≥ 10 mm.

- Distension of central renal pelvis

- More often unilateral but may be bilateral

- No ureteral dilatation

- No bladder dilation or bladder wall thickening

- Size of distension varies

- 35 mm. cutoff important as an indication for neonatal pyeloplasty

- Increased male to female ratio

- Caliectasis may be present

- If obstruction is severe, it may be associated with renal dysplasia (echogenicity and/or renal cysts)

- If obstruction is bilateral, the bladder may be small and amniotic fluid volume decreased

Follow-up

If 5 mm. or greater at < 33 weeks, repeat measurement at or after 33 weeks.

If ≥ 7 mm. after or at 33 weeks, refer for neonatal exam, evaluation, and follow-up.

Above. Patient A. 33 weeks gestation. Bilateral AP diameter of the renal pelvis is 10.0 mm or greater.

Above. Patient A. 33 weeks gestation. Renal pelvis dilatation with evidence of caliceal dilation, but no ureteral or bladder obstruction.

Above. Patient B. 28 weeks gestation. Bilateral renal pelvis dilation of > 10 mm with right side greater than left side.

Patient B. 28 weeks gestation. Same as above. Bilateral renal pelvis dilation of > 10 mm with right side greater than left side.

Above. Patient C. 20 weeks gestation. Bilateral renal pelvis dilation, but no evidence of ureteral, vesical, or outlet obstruction.

Above. Patient D. 28 weeks gestation. Massive renal pelvis dilatation is secondary to UPJ obstruction

Above. Patient D. 28 weeks gestation. Massive renal pelvis dilatation secondary to UPJ obstruction. Color flow Doppler demonstrates normal renal artery to the contralateral kidney.

Uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction.

Above. UPJ Obstruction.

Page Links: Definition, Etiology, Incidence, Associations, Outcome of Unilateral MCDK, Outcome of Bilateral MCDK, Management, Other Reported Associations with MCDK,

(Click on specific reference number for a link to the original abstract or article.)

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK)

Definition

Multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) is a kidney or kidneys with non-functioning irregular cysts of various sizes. The condition is also known as renal cystic dysplasia and Potter type II.

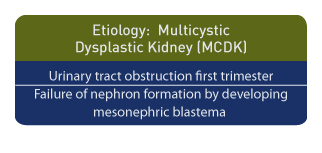

Etiology

A major hypothesis for the development of MCDK is first trimester obstruction of the urinary tract resulting in dysplastic evolution of the kidneys with a variety of clinical and pathological manifestations. [38] An alternative hypothesis is the failure of the mesonephric blastema to form nephrons. [39]

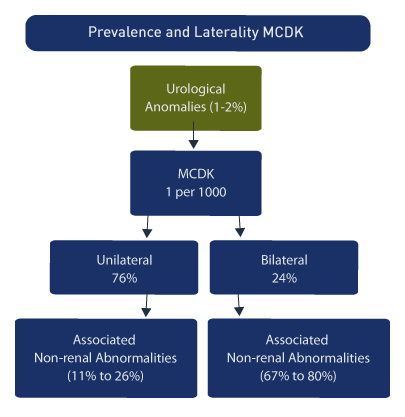

Incidence

MCDK occurs in approximately 1 in 1000 births [2], while the overall incidence of all prenatally determined urological anomalies is 1-2%. Among all fetal urological abnormalities, MCDK is one of the most frequent. [40] In a review of 102 cases of MCDK the following was noted [41]:

Unilateral (76%)

Bilateral (24%)

Associations

A number of associations with non-renal abnormalities are reported [5]:

Associated non-renal abnormalities, unilateral (26%)

Associated non-renal abnormalities, bilateral (67%)

Male to female ratio: 2.4:1

Chromosomal abnormalities: Increased (particularly females)

Females: more likely to have bilateral MCDK.

A wide range of anomalies are possible and may include multiple anomalies of face, fingers, lungs, heart, bowels, and

genitourinary tract. [42]

Prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) increases the background risk overall for congenital malformations by between 4 to 9% and these agents may lead to abnormal renal development and MCDK. [43]

Down serum screening with a value of inhibin A at ?2 MoM is associated with fetal MCDK (OR =27.5, 95% CI: 2.8-267.7). [44]

In addition, Kallmann’s syndrome (anosmia and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism) is described in two siblings with unilateral MCDK. [45]

Making the correct diagnosis and obtaining post mortem studies in lethal cases is important since the risk of recurrence for MCDK is approximately 3% compared with 25% for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). [46]

While familial clusters of MCDK patients are observed, formal screening of relatives is not recommended. [47]

Other reported associations and cases reports associated with MCDK are listed below.

Outcome of Unilateral MCDK

Abnormalities were seen in the contralateral MCDK kidney in 7 of 14 patients and 5 of 14 patients had lethal conditions. Overall, 80% of the bilateral MCDK patients had associated non-renal abnormalities compared with 11% of those with unilateral MCDK. [48] Other studies confirm the poor prognosis with bilateral disease, while involution, reduction, or no change in renal size may be seen in cases of unilateral MCDK. [49]

A mean follow-up of 68 months for 53 children with unilateral MCDK demonstrated the following reassuring outcomes. [50]

2 with hypertension,

5 with urinary tract infection,

90% with involution of the kidney,

17% with complete involution (rate greater during the first 30 months), and contralateral progressive renal hypertrophy.

In 87% of the cases, the unilateral MCDK is non-functioning and outcome is predicated upon renal and/or non-renal abnormalities. [51]

Outcome of Bilateral MCDK

The detection of hydronephrosis and urinary obstruction is improved with the advent of antenatal ultrasound. The use of prophylactic antibiotics can reduce neonatal urinary infections. [52] The increased detection for urinary abnormalities may further improve outcomes by allowing early evaluation, follow-up, and treatment.

Since MCDK can be diagnosed accurately, an appropriate prognosis can be rendered. Those affected with bilateral MCDK, especially those with associated renal and/or non-renal malformations have a relatively poor prognosis and patient counseling is based upon the combination of findings. Severe dysplastic lesions with oligohydramnios and the inability to detect a normal kidney or bladder are usually lethal. [53]

Management

For those with unilateral MCDK, especially those without other renal or non-renal abnormalities, the natural history is usually benign and serial follow up is warranted. [54] The indications for nephrectomy are reserved for complications such as MCDK size or when the kidney continues to increase in size after the second year of life. [55]

Other Reported Associations with MCDK

Below is a listing of other reported associations in addition to Meckel-Gruber (renal cystic dysplasia, central nervous system malformations, polydactylism, hepatic defects, pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios), Trisomy 13 (heart and lung defects, CNS (holoprosencephaly), growth restriction), and Trisomy 18 (growth restriction, cardiac defects, abnormal distal extremities, choroid plexus cysts, omphalocele).

Cystic accessory uterine cavity [56]

Calyceal diverticulum [57]

PAX2 (Paired box protein gene) mutations [58]

Seminal vesicle cyst [59]

Transcription factor 2 gene mutations [60]

VATER (vertebral defects, anal atresia, tracheo-esophageal fistula, and renal dysplasia) [61]

Potter sequence with penile agenesis [62]

Paravertebral arteriovenous fistula [63]

Angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin type 2 receptor gene genotype [64]

Pentalogy of Cantrell (defects involve the diaphragm, abdominal wall, pericardium, heart and lower sternum) [65]

Neonatal Bartter syndrome with polyhydramnios.[66]

Congenital heart defects (7%) [67]

Trisomy 21 [31]

Chromosome 22q11 microdeletion [68]

Trisomy X [69]

Waardenburg syndrome type 1 (varying degrees of deafness, minor defects in structures arising from the neural crest, and pigmentation anomalies) [70]

References

Page Links: Prevalence and Detection Rates, Overview, Ultrasound Findings, Unilateral, Bilateral, Other Ultrasound Imaging, MRI, Differential Diagnosis, References

Prevalence and Detection Rates

The antenatal detection rate for urinary tract abnormalities is increasing [71] and the prenatal detection rate is 97% for unilateral MCDK. [72] In 65 cases of in utero hydronephrosis, 6.2% were recorded as MCDK [73] and in another series of 58 cases of congenital renal malformations, 13.8% were recorded as MCDK. [74]

Overview

Cystic kidneys are an observational finding for a potentially heterogeneous group of disorders and require assessment of family history, both kidneys, liver, associated malformations, and potential syndromes. [75] A prenatal diagnosis is available for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), while MCDK does not affect the liver. [5]

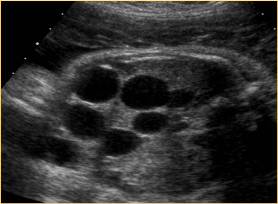

Ultrasound Findings

The typical ultrasound findings in MCDK include multiple anechoic cysts of different sizes and renal enlargement. [76]

In serial ultrasound follow-ups, an initial increase in the size and number of cysts is observed. This is followed by involutional changes, which persist during the pregnancy and into the neonatal period. [77]

The MCDK should be considered a progressive and changing pathology. The larger cysts appear in the early third trimester and after achieving a maximum size begin to regress to small non-cystic masses, which may eventually disappear. [78]

Unilateral

The contralateral kidney in MCDK is significantly larger than expected compared with controls [79] and blood flow to the affected kidneys is normal until the cysts begin to involute. [80]

In addition, in unilateral MCDK the contralateral hyperechoic (echogenicity greater than liver) kidney may be associated with functional abnormalities. [81]

Bilateral

Bilateral MCDK are usually accompanied by oligohydramnios and the constraint changes accompanied by oligohydramnios such as chest hypoplasia, distal extremity abnormalities, and the bladder are not observed.

Other Ultrasound Imaging

Transvaginal ultrasound between 10 and 16 weeks allows accurate early identification of urinary tract malformations. [82]

Inversion mode 3-D volume-rendered imaging provides accurate documentation of MCDK. [83]

MRI

In cases of MCDK, MRI may not provide an advantage over ultrasound. [84] For evaluation of renal parenchyma and assessment of renal function, MRI diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may be of benefit. [85] In 37% of cases in which antenatal ultrasound images of the urinary tract were inconclusive, fetal magnetic resonance urography provided additional information, especially in the evaluation of ureteral anatomy. [86]

Differential Diagnosis

False-positive diagnosis is possible in cases of hydronephrosis with attendant obstruction at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) in which the obstructed calyceal system appears cyst-like. Obstructive hydronephrosis may result in cortical cyst formation. In ARPKD there are bilateral echogenic kidneys and oligohydramnios. Increased ureteral dilatation from any cause may be confused with MCDK.

References

Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney (MCDK): Images

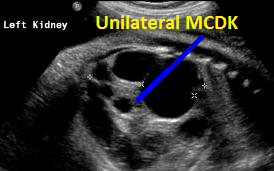

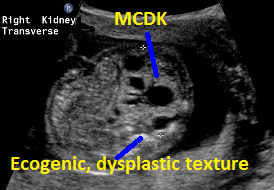

Unilateral MCDK

Above. Patient A. 37 weeks gestation. Transverse. Unilateral multi-cystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK). Multiple cysts of varying size and echogenic kidney.

Above. Patient A. 37 weeks gestation. Sagittal view. Unilateral MCDK. Multiple cysts of varying size and echogenic kidney. Contralateral kidney is normal.

Above. Patient B. Unilateral MCDK. Multiple cysts of varying size and echogenic kidney. Contralateral kidney is normal.

Above. Patient C. Unilateral MCDK with multiple cysts of varying size and some dysplastic changes indicated by echogenic texture.

Above. Patient C. Unilateral MCDK with multiple cysts of varying size and some dysplastic changes indicated by echogenic texture.

Above. Patient D. Unilateral MCDK changes. No other renal malformations.

Above. Patient E. Multicystic dysplastic changes involving only one kidney. While cysts are large, there were no other renal malformations.

Above. Patient E. Multicystic dysplastic changes involving only one kidney. While cysts are large, there were no other renal malformations.

Bilateral MCDK

Above. 37 week gestation. While there are multiple dysplastic cysts, the origin for these changes is pMulti-cystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) disease.

Above. MCDK

Above. MCDK

Back to Toposterior urethral valves.

References

References for Pyelectasis (See below list of references for Imaging Considerations, UPJ Obstruction)

References for Imaging Considerations

References for UPJ Obstruction

-

Abstract: PMID: 1872344 -

Abstract: PMID: 10958739 -

Abstract: PMID: 22710694 -

Abstract: PMID: 22569439 -

Abstract: PMID: 19043723 -

Abstract: PMID: 18256845 -

Abstract: PMID: 19752083 -

Abstract: PMID: 15200251 -

Abstract: PMID: 22428472 -

Abstract: PMID: 15906780 -

Abstract: PMID: 20681980 -

Abstract: PMID: 18280506 -

Abstract: PMID: 16374434 -

Abstract: PMID: 16133060 -

Abstract: PMID: 1872344 -

Abstract: PMID: 17701042 -

Abstract: PMID: 17574624 -

Abstract: PMID: 16550189 -

Abstract: PMID: 22630328 -

Abstract: PMID: 22710694 -

Abstract: PMID: 22744767 -

Abstract: PMID: 18401166 -

Abstract: PMID: 12084278 -

Abstract: PMID: 18074126 -

Abstract: PMID: 15628642 -

Abstract: PMID: 15628642 -

Abstract: PMID: 19043723 -

Abstract: PMID: 19713154 -

Abstract: PMID: 18947602 -

Abstract: PMID: 17296419 -

Abstract: PMID: 15748309 -

Abstract: PMID: 11595845 -

Abstract: PMID: 22469392 -

Abstract: PMID: 22191495 -

Abstract: PMID: 19519760 -

Abstract: PMID: 18708209 -

Abstract: PMID: 22271367 -

Abstract: PMID: 11558015 -

Abstract: PMID: 19065324 -

Abstract: PMID: 9037946 -

Abstract: PMID: 10360509 -

Abstract: PMID: 7832072 -

Abstract: PMID: 17310358 -

Abstract: PMID: 19034930 -

Abstract: PMID: 11390716 -

Abstract: PMID: 18596710 -

Abstract: PMID: 11792949 -

Abstract: PMID: 2188249 -

Abstract: PMID: 17785090 -

Abstract: PMID: 16247543 -

Abstract: PMID: 11876812 -

Abstract: PMID: 2692270 -

Abstract: PMID: 7253115 Oliveira EA, Diniz JS, Vilasboas AS, Rabêlo EA, Silva JM, Filgueiras MT. Multicystic dysplastic kidney detected by fetal sonography: conservative management and follow-up. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17(1):54-7. Abstract: PMID: 11294270

Tohda A, Hosokawa S, Shimada K. Management of multicystic dysplastic kidney detected in perinatal periods. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1992 Oct;83(10):1628-32. Abstract: PMID: 1434265

-

Abstract: PMID: 21113604 Raman A, Patel B, Arianayagam M, Webb NR, Farnsworth RH. Multicystic dysplastic kidney and calyceal diverticulum – more of an association than a coincidence? ANZ J Surg. 2010 Jun;80(6):470-1. Abstract: PMID: 20618213

-

Abstract: PMID: 20358591 -

Abstract: PMID: 19040535 -

Abstract: PMID: 18509286 -

Abstract: PMID: 18075232 -

Abstract: PMID: 17106555 -

Abstract: PMID: 16516609 -

Abstract: PMID: 15470205 Pollio F, Sica C, Pacilio N, Maruotti GM, Mazzarelli LL, Cirillo P, Votino C, Di Francesco D. Pentalogy of Cantrell: first trimester prenatal diagnosis and association with multicistic dysplastic kidney. Minerva Ginecol. 2003 Aug;55(4):363-6. Abstract: PMID: 14581862

-

Abstract: PMID: 12700968 -

Abstract: PMID: 12001193 -

Abstract: PMID: 9988879 -

Abstract: PMID: 9841707 -

Abstract: PMID: 9438657 -

Abstract: PMID: 16053904 -

Abstract: PMID: 18278521 -

Abstract: PMID: 9141757 -

Abstract: PMID: 16174570 -

Abstract: PMID: 1781072 -

Abstract: PMID: 3554210 -

Abstract: PMID: 2188249 -

Abstract: PMID: 3316716 -

Abstract: PMID: 10395135 -

Abstract: PMID: 8234697 -

Abstract: PMID: 1887022 -

Abstract: PMID: 2274490 -

Abstract: PMID: 21790889 -

Abstract: PMID: 9197441 -

Abstract: PMID: 17849498 -

Abstract: PMID: 18631889

54

55

57

65