Transvaginal Ultrasound: Imaging Considerations

Page Links: Measurement Technique Summary, Cervical Length Measurement, Sources of Error, Anatomic and Technical Pitfalls, References

Measurement Technique Summary

Above left. Note the appropriate anatomic landmarks for proper transvaginal ultrasound orientation.

Above right. Note the sequential steps for ultrasound performance. A review of image acquisition and technical performance for transvaginal ultrasound is also provided by these authors: [1]

Above left and right. Follow the imaging sequence as listed above.

Cervical Length Measurement

Above. When the mother is supine, the orientation of the vaginal ultrasound transducer probe in relationship to the position of the maternal feet and head is illustrated as well as the maternal orientation to posterior and anterior.

Above. Standard anatomic landmarks are the bladder, fetal presentation, cervical canal, internal cervical os, external cervical os, and vagina.

Above. Transvaginal ultrasound sagittal view of the cervix with the critical anatomic landmarks illustrated. The gain, zoom, and focal zone should be adjusted to optimize the image and a strict sagittal plane is necessary to image the entire cervix. The cervical canal is imaged horizontally in the middle of the screen, which may not be possible if the cervix is directly anterior.

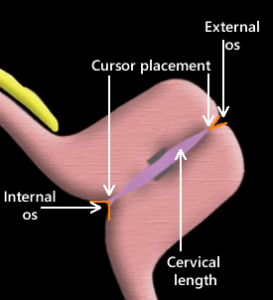

Above. Once the cervical canal is identified, withdraw the probe slightly. Place the measurement cursors precisely at the closing points of the internal and external cervical os and measure the distance between them. For the internal os, a small triangle is often seen. Place the cursor at the apex of the triangle (the closing point). For the external os, follow the posterior cervical lip until the closing point is identified.

Sources of Error

1. Visualize the entire cervix

Above. The entire cervix is not visualized in this example and the internal cervical os and external cervical os is not well defined. Although the cervical length is probably normal, this is a suboptimal image.

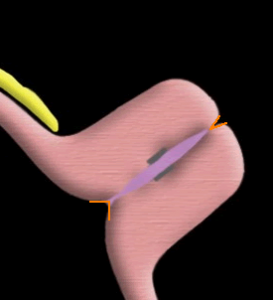

2. Accurate cursor placement

Above. In the image above, the caliper placement is not exact and the distal cervix is not completely visualized, which hampers the recognition of the external cervical os.

3. Excessive probe pressure

Above. Avoid excess pressure on the probe and confirm that the thickness of the anterior and posterior lip of the cervix is the same. In the above example, there is dissimilarity between the thickness of the anterior and posterior cervical lips.

4. Lower uterine segment contractions

Above. Lower uterine segment contractions.

Above. Contractions may lead to an S-shaped canal and asymmetry of the anterior and posterior portions of the cervix.

5. Spontaneous cervical changes

Above. Progressive cervical shortening may occur after transabdominal pressure in patients at risk for cervical incompetence. [2]

Anatomic and Technical Pitfalls

In summary, a number of anatomic pitfalls are recognized and include: an underdeveloped lower uterine segment hampering the identification of the internal cervical os, focal myometrial contractions, spontaneous cervical change, and endocervical lesions such as polyps. [3] Technical pitfalls include incorrect interpretation due to vaginal probe orientation and due to cervical distortion by the probe.

Above. Transvaginal cervical length measurement training. A study shows that those with no prior training can adequately perform the transvaginal ultrasound exam after 18 consecutive ultrasound examinations, while those with experience required only 1 practice session to learn the technique. [4]