Omphalocele: Information

Page Links: Definition, Prevalence, Classification, Risk Factors, Genetics, Management, Differential Diagnosis, References

Definition

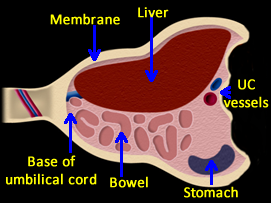

Omphalocele is an abdominal wall defect in which intra-abdominal contents herniate outside of the abdomen at the umbilicus. The herniated organs, which can include fetal bowel, liver, and spleen, are covered by a sac which is composed of amnion and peritoneum. Associated problems, including karyotype abnormalities, are frequent and may affect outcome. [1],[2]

There is a normal physiologic herniation of the fetal bowel at the level of the umbilicus measuring 0.5 cm to 1.0 cm that can be observed as an echogenic mass from 7 to 10 weeks gestation and is no longer seen after 12 weeks gestation. [3] By the fourth week of gestation, the primitive gut begins to develop. Mid-line folding of the embryo results in fusion of the abdominal wall. When fusion fails to occur, an abdominal defect develops and the abdominal organs protrude into the amniotic cavity. The resultant defect may be covered or uncovered.

Prevalence

The prevalence rate for omphalocele is reported at 1.6 per 10,000. [4] In general, the prevalence rate for anterior abdominal wall defects is increasing, but is greater for gastroschisis than for omphalocele. [5]

In Japan, the incidence of omphalocele was 0.322 per 10,000 births in 1975 to 1980 and 0.626 per 10,000 births in 1996 to 1997. [6] The prevalence rate varies by gestational age and by maternal age. [7] The prevalence of omphalocele in a population with the maternal age distribution of all deliveries in England and Wales was 7.4 per 10,000 at 12 weeks of gestation, and 3.5 per 10,000 at 20 weeks, and 2.9 per 10,000 in live births.

Classification

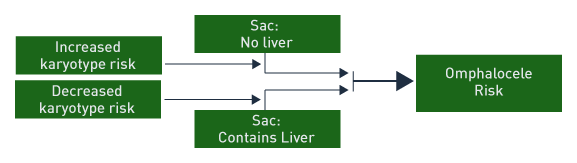

When the omphalocele sac contains only bowel and there are associated anomalies, a high risk is present for chromosomal abnormality and poor outcome. When the omphalocele sac contains only liver, the outcome is generally good with a low risk of chromosomal abnormality. [8]

Small omphalocele size correlates with an increase in gastrointestinal anomalies, but a lower risk for cardiac anomalies. [9]

Risk Factors

Above. Risk factors and associations with omphalocele can be broadly categorized into 4 entities. Multiple congenital anomalies (non-syndromic), karyotype abnormalities, malformation complexes, and non-chromosomal syndromes. [10],[11]

Risk Factors for Omphalocele

Associated malformations (74.1 %).

Abnormal karyotype (29.3%).

Recognizable syndrome or an unspecified malformation pattern (44.8%).

Oligohydramnios.

Polyhydramnios.

The above risk factors and their relative frequency have been identified for omphalocele. [10]

Non-chromosomal Syndromes Associated with Omphalocele

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

Goltz syndrome.

Marshall-Smith syndrome.

Meckel-Gruber syndrome.

Oto-palato-digital type II syndrome.

CHARGE syndrome.

Fetal valproate syndrome.

Malformation Sequences Associated with Omphalocele

Ectopia cordis.

Body stalk anomaly.

Exstrophy of bladder.

Exstrophy of cloaca.

OEIS (Omphalocele, Exstrophy of bladder, Imperforate anus, Spinal defect).

Malformation Complexes Associated with Omphalocele

Pentalogy of Cantrell.

Multiple Congenital Anomalies (MCA) Associated with Omphalocele (30.2%)

Musculoskeletal system (23.5%).

Urogenital system (20.4%).

Cardiovascular system (15.1%).

Central nervous system (9.1%).

These tables suggest associations and risk for omphalocele and the relative frequency of associations of MCA with omphalocele. [11]

Genetics

Among 256,858 births, 29.3 % of fetuses with omphalocele had an abnormal karyotype. [12] Other studies report similarly high abnormal karyotype rates of 17% and 20%. [13],[14] However, the rate of chromosomal aneuploidy is reported higher (8 of 17 or 47%) when determined between 11 and 16 weeks. [15] In addition, if the sac contained the liver, the karyotype was normal in this study. [15] Abnormal nuchal translucency and small sac size suggested a higher risk for abnormal karyotype. [15]

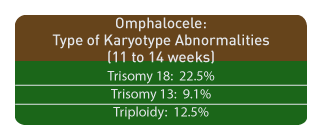

Among 15,726 viable, singleton pregnancies at 11-14 weeks of gestation, omphalocele was diagnosed in 0.11% of the cases. The combined frequency of trisomy 18, trisomy 13, and/or triploidy was 61%. The corresponding frequencies of omphalocele for fetuses was as follows:

Trisomy 18, 22.5%.

Trisomy 13, 9.1%.

Triploidy, 12.5% [16]

The prevalence of omphalocele among a population depends upon maternal age and gestational age at the time of diagnosis. [16]

Outcome

Survival rates with omphalocele depend upon the presence of associated chromosomal abnormalities or associated malformations. The most frequent karyotype abnormality is trisomy 18.

Survival

When chromosomal abnormalities are excluded, the survival rate for isolated omphalocele is reported at 44% (7/16). [17]

Associated Malformations

Irrespective of the karyotype, most series report a high rate of associated malformations: 26/33 (78%), 96/127 (76%), and 21/26 (81%), [18],[19],[20] and outcome is related to the type of anomaly. [21]

Other Factors Related to Outcome

Other factors related to outcome in fetal omphalocele:

Small sac size (higher prevalence of gastrointestinal anomalies). [22]

Premature delivery (14 of 27 fetuses or 52%). [21]

Fetal growth restriction (4 of 11 or 36%). [21]

Contents of sac: Liver and bowel versus bowel only. [23]

Liver and bowel (Associated anomalies, 7 of 20 or 35%).

Bowel only (Associated anomalies, 17 of 19 or 93%).

Liver and bowel (Chromosomal abnormalities, 1 of 17 tested or 6%).

Bowel only (Chromosomal abnormalities, 17 of 19 or 93%).

Liver and bowel (Survival, 14 of 39 or 36%).

Bowel only (Survival, 1 of 19 or 5%).

Management

Prenatal Management

Prenatal management involves serial assessment of the fetus for diagnosis, follow-up, and testing. [24] Amniocentesis for karyotype is indicated. Given the possibility of associated cardiac malformation and fetal growth restriction; targeted scan, cardiac echo, and follow-up scans for growth are indicated while fetal testing with biophysical profile on a weekly basis seems warranted. Delivery at a tertiary care center with a multi-disciplinary team is optimum. Route of delivery with small omphalocele does not alter outcome. [25]

Neonatal

Neonatal surgical management of these defects is not uniform or standardized. [26] Obvious variables in the success of surgical repair depend upon the defect size, the contents of the sac, the presence of karyotype abnormalities, and the type and extent of associated malformations. Primary closure versus delayed closure is an initial surgical decision. If closure is delayed due to the defect size, a variety of techniques are reported which include the use of synthetic versus biomaterial patches. [29] The latter include solvent-dried dura biomaterial grafts which promote rapid scar formation, and integration with adjacent skin tissue with the effect of reduced foreign body reactions at the site of implantation. [27] Other techniques include the use of prosthetic mesh, and silastic sacs, but small bowel obstruction during the first year of life occurs and can be fatal irrespective of the method chosen. [28]

Neonatal Management of Giant Omphalocele

Giant omphaloceles are defined as a liver containing protrusion through an abdominal wall defect which is wider than 5 cm. [29] These lesions are less likely to be associated with karyotype abnormality, but their size presents a surgical challenge and complications are reported such as liver infarction and respiratory insufficiency. [32],[30] Prolonged ventilator support may be necessary. [31]

Specific surgical approaches and techniques for closure are:

Intraperitoneal tissue expander (IPTE) to create adequate abdominal domain. [32]

Progressive stretching of the abdominal wall and enlargement of the abdominal domain. [33]

Tissue expanders positioned in the potential space between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis layers. [34],[35]

Component separation technique. [36]

Sequential sac ligation. [37]

Translation of the muscular layers. [38]

Vacuum-assisted closure. [39]

Bilateral longitudinal fibroperitoneal-aponeurotic transposition. [40]

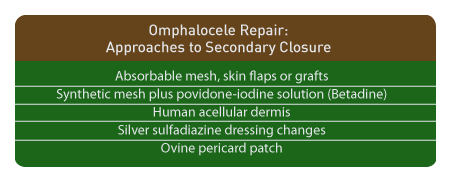

In addition to the above, specific approaches to allow secondary closure and delay primary repair are as follows:

Absorbable mesh followed by split-thickness skin graft. [41]

Synthetic mesh plus povidone-iodine solution. (Betadine) [42]

Human acellular dermis. [43],[44],[45]

Silver sulfadiazine dressing changes. [46]

Absorbable mesh and skin flaps or grafts. [47]

Bovine pericard patch. [48]

Differential Diagnosis

References

Abdominal wall defects. Aspelund G, Langer J. Current Paediatrics. 2006;16(3):192-8. Prenatal diagnosis of anterior abdominal wall defects: pictorial essay. Agarwal R. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2005;15:361-372. -

Abstract: PMID: 2945223 -

Abstract: PMID: 8475457 -

Abstract: PMID: 15280125 -

Abstract: PMID: 10646777 -

Abstract: PMID: 8590187 Outcome of fetal omphalocele according to omphalocele content combined with associated anomaly. Jung SI, Cho JY, Ryu JK. J Korean Soc Med Ultrasound. 2005 Jun;24(2):61-6. -

Abstract: PMID: 19040938 -

Abstract: PMID: 11755106 -

Abstract: PMID: 18386803 -

Abstract: PMID: 11755106 -

Abstract: PMID: 18204766 -

Abstract: PMID: 15754571 -

Abstract: PMID: 9203209 -

Abstract: PMID: 8590187 -

Abstract: PMID: 17674424 -

Abstract: PMID: 19215546 -

Abstract: PMID: 15266212 -

Abstract: PMID: 17985136 -

Abstract: PMID: 16580922 -

Abstract: PMID: 19040938 Outcome of fetal omphalocele according to omphalocele content combined with associated anomaly. Jung SI, Cho JY, Ryu JK. J Korean Soc Med Ultrasound. 2005 Jun;24(2):61-6. -

Abstract: PMID: 18634119 -

Abstract: PMID: 11704185 -

Abstract: PMID: 18414971 -

Abstract: PMID: 12152643 -

Abstract: PMID: 18358285 -

Abstract: PMID: 16308903 Challenges of giant omphalocele: from fetal diagnosis to follow-up. Davis AS, Blumenfeld Y, Rubesova E, Abrajano C, El-Sayed YY, Dutta S, Barth RA, et al. NeoReviews. 2008;9(8):e338. Link: http://neoreviews.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/neoreviews;9/8/e338

-

Abstract: PMID: 17323674 -

Abstract: PMID: 16567180 -

Abstract: PMID: 15795823 -

Abstract: PMID: 15065039 -

Abstract: PMID: 15544772 -

Abstract: PMID: 18206491 -

Abstract: PMID: 16865514 -

Abstract: PMID: 15803336 -

Abstract: PMID: 16410135 -

Abstract: PMID: 15213910 -

Abstract: PMID: 17043872 -

Abstract: PMID: 16490981 -

Abstract: PMID: 16516614 -

Abstract: PMID: 16410136 -

Abstract: PMID: 15300551 -

Abstract: PMID: 17101356 -

Abstract: PMID: 12720180 -

Abstract: PMID: 17628735

1

2

8

23

30